Index IndexPage |

Previous Previoussection |

Section 2 |  Next Nextsection |

The birth of the Mennonite Brethren Church was not born without difficulty receiving opposition from both the established church and civil authorities. Menno Simons (ca 1496 - ca 1561), a Roman Catholic priest, gave up his priesthood in 1536 and embraced the views of a group known as the Anabapistists in the Netherlands. There were known as the 'brethren' to avoid the stigma of the name 'Anabaptist'. Only after his death did they become known by the name of 'Mennonites'. They were granted freedom of religion in 1676.

The Mennonites did, however, share some common doctrinal beliefs with the Anabaptists such as

- The authority of the Bible as the final and infallible rule for faith and practice.

- The church was to be a group of regenerated (born again) believers in contrast to the state church who believed membership made one a Christian in the sense of being born again.

- Baptism was done by immersion.

- Finally, they opposed infant baptism.

Although Catherine II, the German wife of Peter III gave an invitation to the Germans and other Europeans in 1762-63 to settle in the area vacated by the defeated Turks in Southern Russia, the Mennonites did not migrate until the 1780's. The French Revolution had failed and increasing military preparations in Prussia made the Mennonites nervous. Non-resistant by nature, government taxes were based on land ownership which in turn contributed money to military and church (state) taxes, but the Mennonites did not wish to support either of these functions.

This created a major problem. The more land the Mennonites owned, the more money the government lost that could have been contributed to the support of state functions. To keep them from gaining more land, the government slapped controls on the Mennonites which kept them from buying more land. This put young couples desiring to start their homes into a state of being landless. It has been said that a Mennonite without a farm is like a horse with a rider.

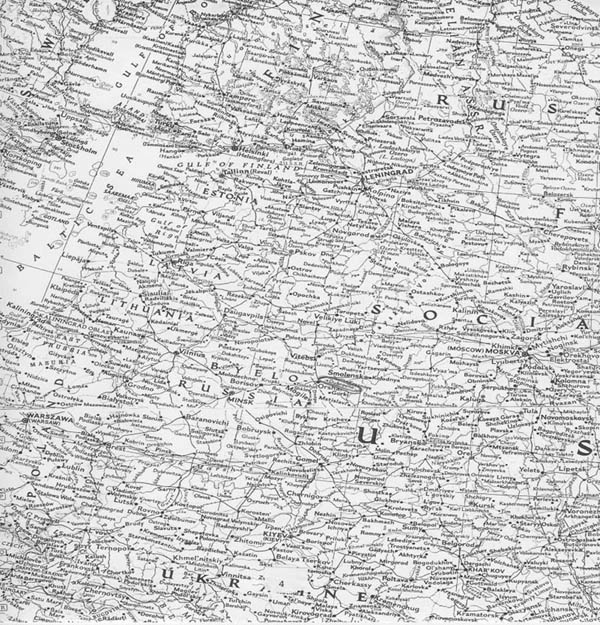

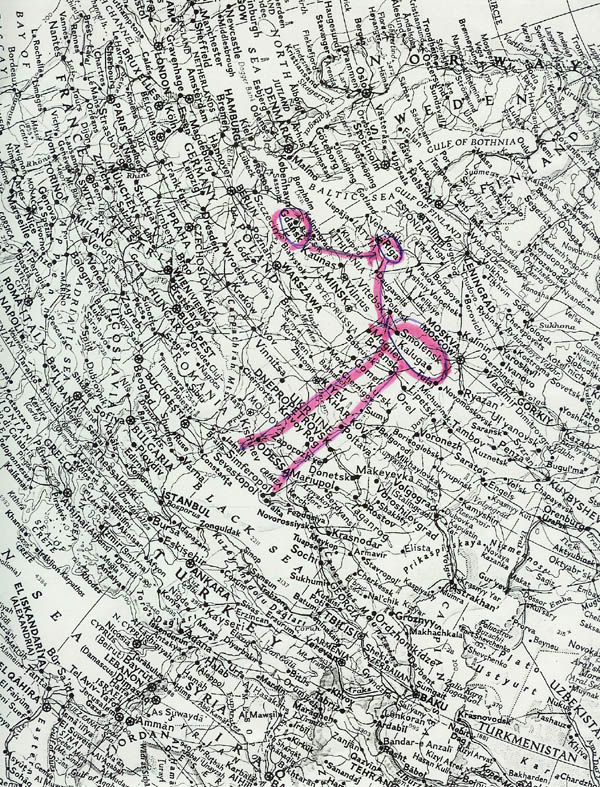

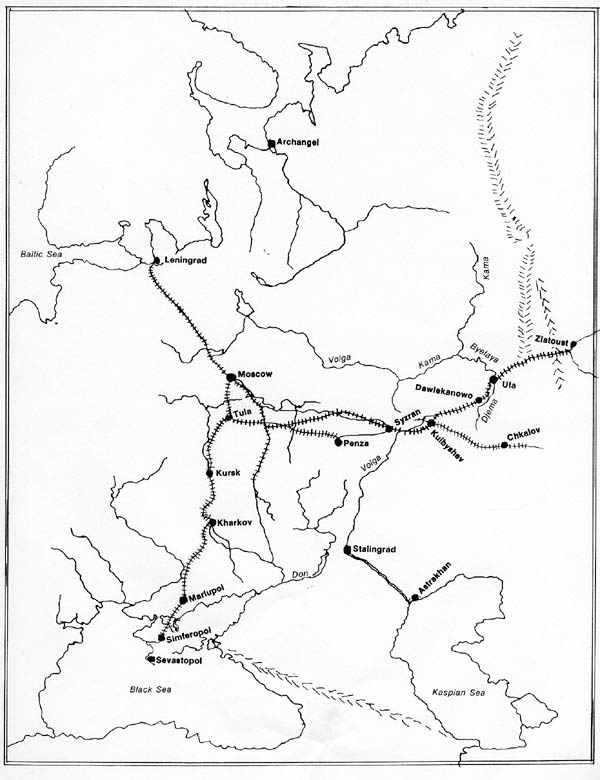

The first group to come consisted of eight families totaling about 50 people. It took them five weeks to travel less than 300 miles from Danzig (now renamed Gdansk, Poland) to reach Riga (now the capital of Latvian). With a month off to rest their horses, it took them another six weeks to travel the next 300 miles to reach Dubrovna (see maps page 6 and 7). They were forced to winter there (Dubrovna) because Russia was at war with Turkey. By the following year when they were free to travel, there were some 228 families in their camp waiting to go further.

Oddly enough in this first group there was not a single minister. To complicate this obstacle further, there were also twelve couples who desired to become married. An offering was taken to send back to Danzig along with a petition to send them a minister. The Danzig church replied by telling them they should conduct their own elections for a minister. Of the twelve names given to Danzig, four were approved, of which Bernhard Penner was one, and commissioned by letter to serve as elders.

The first colony at Chortiza was made up of 400 families on the Dniepr (Dnieper) River in the Ukraine. Living conditions, to say the least, were difficult for these first pioneers. They lived in mud huts which in the rain became even muddier. They also experienced material lose. Their horses were either stolen or lost due to the lack of fences. Their lumber was of inferior quality and the families were dirt poor. Disease and death also took its toll on them. Nor did not receive of the financial aid promised them for up to eight years plus there was disunity in the camps. These were just a few of the problems they experienced. Nevertheless by the early 1800's these 400 families had become established into fifteen villages and were farming about 89,100 acres of land.

Coming into Russia they were granted special concessions in 1788 enabling them to control their own religious, educational and civic concerns pretty much as they had done in Prussia. They were also granted COMPLETE freedom of religion and exemption from the military for as long as they were there. When one colony ran out of land, daughter colonies were established in new areas.

The Mennonite Brethren Church, itself, was born on January 6, 1860. A pietist named Eduard Wust of Lutheran background conducted meetings among the Mennonites in Molotshna stressing repentance and conversion leading many Mennonites into a personal relationship with Jesus Christ. He led them whenever possible in Bible studies and prayer cells. Though unrelated at first, this revival starting first in the Molotschna colony spread to the Chortitza colony.

Pietism was a reform movement in Lutheran circles that stressed personal religious feelings. Evangelical in nature, they had a profound effect on 17th and 18th century Christianity in Europe. They stressed personal internal religious experiences rather than outward conformity to the church dogma and practice. They believed in the rebirth of mankind in Christ and regarded the church sacraments as symbols rather than the means of grace.

Trying to bring renewal among their own people who had become apathetic in spiritual matters was another challenge they faced. They became discouraged by their fellow Mennonite's lack of interest and were accused by the mother church of being unspiritual. This led to the estrangement and separation between the Mennonites and the newly formed Mennonite Brethren.

Finally they chose to interpret the scriptures for themselves rather than solely depending on the clergy to do this for them.

One of the touchy issues was the matter of communion. Under the dictates of the Mennonites, communion was to be administered only by the church elders and not by lay people. In 1859 under the direction of Abraham Cornelsen, a schoolteacher, a private communion was held with none of the church elders present.

Disciplined by the elders, they (the Brethren) agreed never to do such an irregular thing again promising obedience to all things not contrary to their conscience and the Word of God. The elders worked toward reconciliation but the Brethren as they were known (they addressed each other as 'Brother') felt they could no longer fellowship with the membership of the mother church.

At a private meeting on January 6, 1860, Abraham Cornelson put a document before those present, fully aware that if they signed it, - they could face persecution - calling for a formal separation from the Mennonite church. This document was signed by 18 people that day. Nine others signed it a day or so later.

This document charged the Mennonite church with growing corruption and its leaders for allowing their spiritual condition to decay. They were in agreement with their basic doctrines but it was the church's decline in spiritual matters that was their main concern.

The church elders denied these charges and placed this matter in the hands of the colony's civil authorities. They wanted the Brethren to 'see the error of their way' and be returned to the church by force.

Colony administration asked the Brethren for an explanation. They responded on January 23rd stating that they would have gladly remained in the in the church IF their ministers were obedient to the Word of God, but since they weren't, they had no choice but to leave. They also firmly stated it was their intent to remain Mennonites.

Under the Penal Code of 1857, the administrators treated them as a secret society and all meetings not sponsored by the established church were forbidden. Abraham Cornelson, a father with a large family, was banished to live among a nomadic people for a time. Others were ruined economically with legal travel documents being denied them. Thus they became prisoners in their colony. They were not allowed to leave and officials made their staying unbearable.

The M.B. group fought for government recognition which in turn would also force the church to recognize them, but on the other hand, if they failed, they could lose their special privileges.

Government officials were friendly and helpful to them in their contact with the Baptists.

The church at Molotschna was given two options by the colony authorities: expel the Brethren or grant them recognition.

Refusing to accept this civic action of the church, the Brethren sent a petition to the Czar in the spring of 1862 to so something on their behalf. In October of 1862, the General Conference agreed to accept them on the condition that the confession of their faith was the same as theirs.

Hoping that the church would set the wheels in motion for expulsion and disappointed that they did not, in an attempt to suppress this movement, the colony administrators in 1863 ordered the village officials not to recognize marriages performed by the Brethren and to record all births in the name of the mother treating them as illegitimate.

The government answered their petition on this latest uproar on March 5, 1864 by formally recognizing them as Mennonite Brethren in the full sense of the word. Despite the division between the two groups, the two churches started to work together on matters of common interest. This was the church that the Wiens-Pauls family grew up in.

The history of the Ufa colony pales in comparison to the two original colonies but bears stating. Ufa is located in the northwestern part of the Urals (see map on page 12). The capital city of Ufa was Ufa, which was the center of political and social activity. The price of land was cheaper there then in Southern Russia, and unless they received financial assistance from their fathers, young beginning farmers could not afford to buy land in the original colonies.

Therefore it was mainly young families who decided to move northward and arrived in the Ufa area during the time period of 1894 to 1901, though some came earlier and others later. The parents of our Peter Wiens were among those early pioneers. These pioneers came from such places as Altsamara, Neu Samara (the birthplace of Maria Eck) as well as the original mother colony - Molotschna. They came from all walks of life - mill owners, machine manufacturers, merchants, farmers, etc.

Index IndexPage |

Previous Previoussection |

Section 2 |  Next Nextsection |